True American Cowboy

Bill Scott Featured in: American Cowboy July/August 2006

HARD TO REPLACE

BILL SCOTT KNOWS THE VALUE

OF A GOOD HORSE,

A GOOD CUSTOMER,

AND A WAY OF LIFE.

BY J.P.S. BROWN

Cowboys who don’t belong anywhere and drift job to job often find themselves out of cow work, so to stay horseback while they earn their beans they sometime wrangle dudes. The world will never run out of people who want to ride with a cowboy and see the West from the back of a horse.

The livestock of the dude business demands the same care as cows do. Heifers and dudes in season act much alike. Bulls and dudes can be overbearing, arrogant, willful, and foolish. It’s easy to run the fat off a dude as it is a choice steer or heifer, but the cost per pound gain of a dude is a whole lot higher than that for the bovine. Little dudes beller and the big ones bawl for about the same reasons cows and calves do. They all need shade when they’re hot and shelter when they’re cold and extreme weather, bunching, and chousing makes them hard to hold.

However, in some ways, a dude is easier to handle than a cow. A dude rarely stampedes, hooks a feller with a horn, tromps him, cow-kicks him, blows slobbers on him, or splatter him, with nasty things, and almost never tries to get away.

Dudes are at least as entertaining as cows, even when they don’t mean to be. A cow can’t voice that honestly curious question that turns a poor cowboy into a laughing fool the way a dude can. Probably nothing in the world can move a cowboy more than a newborn calf’s clean, good looks and actions, unless it’s the look of awe on a little dudes’ face the first time it sees a cowboy on a horse. And for a wrangler, the sight of a tiny fellow human on a great big horse and the sound of squeals of fun can move him about as much as anything in the world. To be on hand to catch an old human and hold him on his horse, just before slumber unseats him and he falls asleep in a tailspin to the ground, is as least as rewarding as walking an old bull to shelter during a blizzard. So, wrangling has its perks.

A cowboy who thinks he knows it all and can’t learn more about making a living horseback, has reached his peak, as a cowboy and as a person. Anyone who thinks he’s too good to be a servant, doesn’t have an idea how honorable it is to serve an animal or a person.

A cowboy serves his cattle’s needs and a wrangler serves the dudes, and anybody who can’t be proud to do that does not know how good it is to be a gentleman.

His willingness to serve in the honorable husbandry of his own kind is how the cowboy came to be known as a gentleman. That’s how the Spanish term caballero literally translates as horseman, it is no other meaning in Spanish except as the definition of a gentleman, because the man on a horse has proven through the centuries to be a gentleman who serves his own kind with honor.

The big difference between the husbandry of cattle and the husbandry of people might only be moral. It’s hard to morally offend the bovine, but a cowboy can run into a lot of trouble if he offends a dude. Dude wrangling could conceivably send a poor cowboy’s soul off to perdition, if he doesn’t watch it. But then, the reward for being a good wrangler also might be a crown in heaven if he puts up with the dudes just right. There probably won’t be any reward for a cowboy who spends his entire life only looking after cattle. He will undoubtedly cuss and strangle the bovine too much to go to heaven, at least without first being awfully punished. Nobody can be sure what his punishment could be, but if he were asked what he deserved, he’d probably say it was holding herd for 16 trillion years on a horse that got tired the first minute after he came on watch.

“Wrangler” comes from the Spanish word caballerango. Literally, it means ranking horseman, head horseman, master of the horse. Cowboys made the “rango” part into “wrangler” and defined it as anyone who looks after horses.

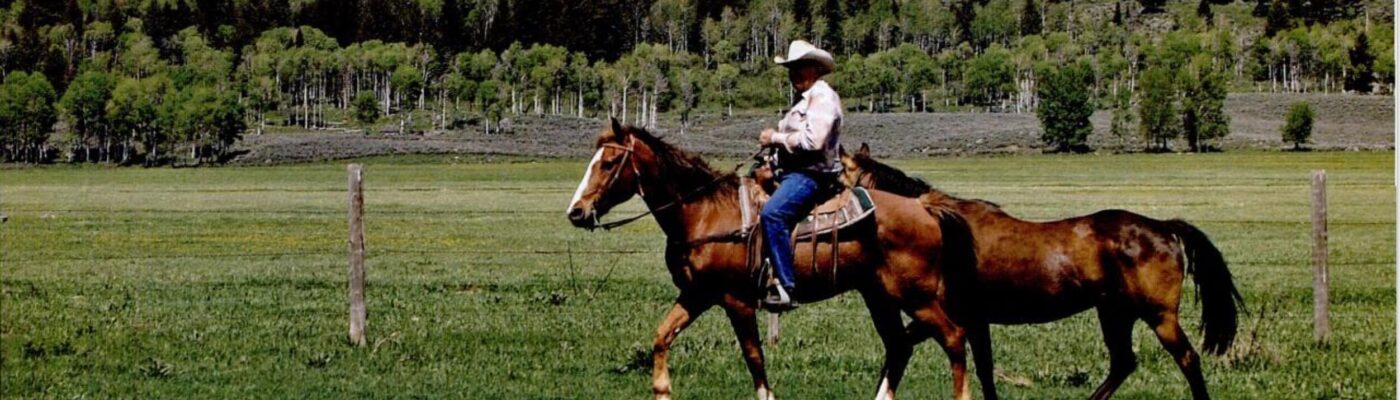

By any definition of caballero, or wrangler, Bill Scott of Jackson Hole, Wyo., has achieved this mastery, because almost every day for 70 years he has given a hand to people and horses. Scott rides good horses. Any horse that spends his lifetime carrying every kind of size, shape, and disposition of a person without killing even one, is a good horse.

Any horse that can stay under every shape and size of human when every surface of the human is soft and round and keeps trying to roll off, is a good horse. A horse that has been in Bill Scott’s string for at least a year can be taken away and taught to service the needs of any other kind of horseman. If any man can be known as a good man by the horses he rides, he is Bill Scott.

Born in Gillette, Wyo., in 1934 to Harold and Bertha Jane Anderson Scott, Bill grew up as a cowboy. Harold Scott came from Missouri with his folks who homesteaded their cattle ranch near Gillette in 1914. Bertha Jane’s people were from Iowa and homesteaded a sheep ranch that neighbored the Scotts’.

Scott has three brothers: Marion of Gillette, who still runs the family ranch: Jim of Cottonwood, Ariz., and Doug of Buffalo, S.D. Jim is an auctioneer. Doug is a saddle maker for the Circle Y Saddlery of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Scott’s sister Kay lives in Queen Creek, Ariz.

Scott has not done any cowboying since he left home in his teens, although he stills thinks like one. “I grew up chasing cows,” he said. “So, it don’t take much to keep me busy.” He and his brother broke and trained their ranch’s cowhorses. “Once, we started one we stayed on him until he was made,” Scott said. “Our only fun was helping Dad with cattle. We didn’t compete in sports, just cowboyed and rodeoed. My favorite event was saddle broncs.”

From 1952 until 1965 Scott belonged to the Northwest Ranch Cowboys Association. He won the All Around Championship at Buffalo, S.D. as a senior in high school. Spec Hettinger of Miles City, Navajo cowboy Bobby Singer of Kayenta, Ariz., and Dave Force of Gillette traveled with him. He was called into the U.S. Army in 1957 and shipped to France. He won the All-Around in an inter-service rodeo south of Paris. “I entered another rodeo in Belgium, but didn’t do any good,” he said.

One night, as they traveled between the Sheridan (Wyo.) and Deer Lodge (Mont.) rodeos, Scott and Hettinger stopped in Yellowstone Park and rolled out their bedrolls to rest. Before first light, Scott felt something pull on his bedroll tarp with too much enthusiasm. Thinking Spec was being overly insistent about getting him up, he whacked him on the side of the head, then discovered he had slapped a bear. Incensed, the bear ran away.

“If anything can take a man to a cow, it’s a horse, and if anything that can take a man away from a cow, it’s a horse. I didn’t much want to return to the ranch after the service, so I decided to earn a real living in this world with horses,” Scott said.

In 1963, he opened a riding stable at The Virginian Motel In Jackson Hole and took summer trail rides into the Snow King ski area. The same year he walked into the offices of the National Park Service on business and met its receptionist, Vonona “Sam” Bailey of Cheyenne. “I thought she might help me get through Park Service red tape, but she worked out in other ways,” Scott said. “In 1968 Wonderful Sam married me.”

“I found other ways to keep my horses busy by contracting government jobs in the parks and forests,” he said. “We furnished packhorses, crews, and equipment that sprayed trees with insecticide to kill the pine beetles in the forest. We also did trail maintenance. We worked three jobs at a time and used three men and 25 horses on each job.”

In 1965 he bought property on a stretch of the Salt River at Tempe, Ariz., and established the wintertime Papago Riding Stable. That same year he opened a summer stable at Teton Village, under the Grand Teton Mountains. Both stables are still run by the Scotts. He started furnishing stock, driving teams, and acting in bit parts for the movies in the early 1950s and continued until Westerns dried up in the 1990s. His first job was as a horseback extra in Road to Denver, starring John Payne. He furnished horses on the Sacketts, Three Amigos, Tombstone, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and John Wayne’s Red River. “Wayne liked to spend time around our horses to get away from people,” Scott said. He got a speaking part that led to his getting a Screen Actor’s Guild membership when he drove the stagecoach that Lee Marvin held up in Cat Ballou. “Whoa,” he said, and stopped the coach.

In a scene on the Outlaw Josie Wales, Clint Eastwood was supposed to ride down a Mezcal, Ariz., street, but his horse spun around, ran back to the corral, and dumped the actor against a gate. “I sure thought he was hurt,” Bill said. “But it turned out he wasn’t. I put him on one of my horses and he did the scene with no trouble.”

Scott and his horses made good names for themselves among movie makers. One day Harry Taylor, who drove Scott’s stagecoach in the streets of Jackson every summer for many years, knew every cowboy in the West, and could recite by heart every cowboy song and poem ever written, called Scott over to introduce him to a cowboy actor Ben Johnson. “Do you two already know each other?” Taylor asked. “I don’t know if Bill knows me,” Johnson said, “But I sure know Bill.”

Scott and Sam have seven children, including two sets of twins, and 10 grandchildren. All of them helped with the horses as soon as they got big enough. At present, Clay, Wayne and Shane and daughter Jodi work steady. Jayne, Shelly and Kelly are married and live elsewhere, but often come home to help.

Wayne sent to Smithsonian Institute for blueprints for what would be his single-handed construction of a stagecoach and, after six years, about had it finished. This, after two hip transplants, a kidney transplant, and spine surgery. His brother Shane gave him a kidney in 1999.

The Salt River was dammed up to catch water in 1998 and Papago Stables now lies only a few yards above the marina at Tempe Town Lake. The Scotts take their rides into the 2,500-acre Papago Park reserve. Donated to the city of Phoenix by the family of George W. P. Hunt, first Governor of Arizona, the park is reserved forever for public horseback riding.

City, state, and federal governments have tried to remove the Scotts from their property several times. “It looked bad for a while,” Sam Scott said. “Our property has been condemned to make way for a river channel, for a bicycle path, for a wildlife refuge, and to make room for a condominium development.”

Oldest Son Clay said that the dudes help the family keep its sense of humor. “We once took 10 Fiesta Bowl football players for a ride,” he said. “After we got lined up, I looked back, and calculated that our ten horses had to carry a ton and a half of football players.”

“Riders on the Grand Teton National Park look up at the glaciers on the mountains and ask if they are real,” Shane Scott, the youngest son, said. One asked me, “What’s that white stuff made of, cotton?” Another asked me, “When do the Elk turn into moose?” When they noticed a certain rock slide by the trail they asked, “Who arranged those rocks that way? Did somebody have to put them there to make them look like that?”

My dad handles dudes better than anybody. He has three-hour conversations with people he doesn’t even know. We have guests who’ve been riding with us for 25 years. They bring friends and ask my dad to tell them his good old stories. When they ask if there are bears on the trail he tells them the story of his Yellowstone bear.

We like to tell about the day our dad needed to brand a horse. The Brand Inspector was enjoying the fireplace and drinks with Mike Craft and some of Dad’s other cronies in the bar of The Virginian. Dad led his horse into the bar, heated the branding iron in the fireplace, branded his horse, then branded the wall for good measure.

The only time Scott can be sure his riders will stay out of trouble is while they’re aboard his horses. “I like to hire cowboys because they have good sense, even though some invest too much in houses and lots,” he said. “That’s bawdy houses like Nevada’s Mustang Ranch and lots of whiskey.”

Scott says that dudes sometimes get themselves in trouble when they’re away from home, like anyone else. He gave this illustration: Once, the wife of a guest called him from Sacramento to complain that his horse rental was exorbitant. “What do you mean?” Scott asked her. “That check my husband gave to the Mustang ranch was an awful lot to pay for the use of one old horse, don’t you think?” the woman asked.

“Poor judgment causes more horse wrecks than anything,” Scott said. “We’ve been lucky. In the 40 years we’ve been in business, we’ve never had a bad accident. However, when dudes and wranglers bunch up, other kind of accidents happen, to the dudes’ greatest peril. One dude lady who came to ride with us at Jenny Lake, Wyo., ran off with our wrangler. When I ran into the lady again in the fall, she said, “Can you believe it? I came out West in a $40,000 car, took off with the wrangler, and went home penniless in a $100,000 bus.”

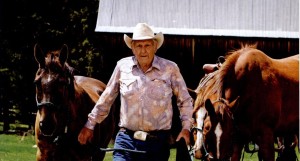

Scott’s sensible and foolproof horses stay honest and never run off with anyone. “Our old Spud horse is close to 30 years old, but he’s still a good keeper, is a gentle and smooth saddle horse, and a good single-buggy horse. Recently somebody offered me $5,000 for him, but I figured he made that much last year alone. I can’t let anybody run off with him. He’d be too hard to replace.”

Recently, a pacemaker was installed to keep Scott’s old heart in line, but it didn’t work too good. He had to have it started up again. “Lately, the only way I’ve been able to keep up with Wonderful Sam is to cut across and head her off, but she hasn’t threatened to replace me, yet,” he said.

J.P.S. Brown, real border cowboy and writer passed in 2021. His Arizona series of novels was recently re-issued by the Authors Guild and iUniverse, Inc., Lincoln, Neb.

Post Script: Bill has since passed and the family is dedicated to keep his legacy going. He was truly an amazing man and an icon in Jackson Hole as well as Arizona.